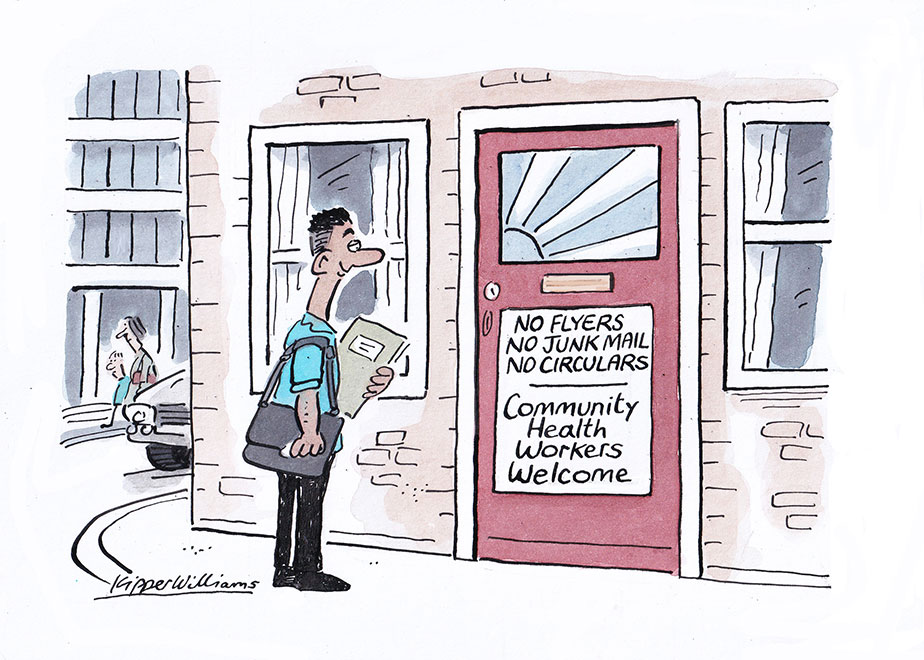

For patients in Westminster, a knock at the door may not be a typical cold caller. It could be one of the community health workers who are part of an ongoing trial in the London borough to promote preventive medicine and tackle health inequality.

The Community Health and Wellbeing Workers Programme is a British counterpart to a Brazilian model first introduced in the 1990s.

Community Health and Wellbeing Workers (CHWWs) receive basic training to conduct simple health checks and handle conversations. They work with a list of households in their local area, going door-to-door, regularly speaking with residents and, where they think they could be beneficial, connecting them to support services in their area.

First and foremost, the role of a CHWW is to establish and develop trust with residents. They can speak with patients about what challenges they might be facing with their health and discuss the services available at their local GP practice, including appropriate health checks and screening.

"The aim is to increase the prevention opportunities in primary care," explains Dr Connie Junghans Minton, a GP at the Millbank Medical Centre who, alongside Dr Matt Harris - a clinical reader in public health medicine at Imperial College London - is spearheading the programme in Westminster.

"The service landscape can be too reactive. Many people aren't reaching out at the point it's easiest for us to treat them,” explains Connie, “we aim for universal access, we approach all patients locally, assess and connect with relevant services, rather than target for the highest impact and end up picking up people at the sharp end."

The scheme was first trialled by the local authority in the Churchill Gardens Estate in Pimlico. It showed an astonishing increase in prevention opportunities being accessed and was handed over to GP practices in the area. It now has 25 full-time CHWWs working across 76 ‘villages’ - each a collection of 120 households - in Westminster"

“We've expanded the number of practices adopting health workers. We've seen really positive results so far, and we've had great feedback from both our patients and the health workers who make the initiative possible," says Connie.

While Westminster is one of London's most affluent boroughs, there are significant health inequalities. "The difference between the wards of the borough with the highest and lowest life expectancy is 18 years for men," Connie explains.

"One of my patients has a diagnosis of dementia and lives on his own, without a strong support network. He has diabetes and heart issues, and his dementia can mean he forgets to take his medication, which causes his health to rapidly deteriorate. Visits from CHWWs means he can at least get some support at home and contact with services that he would find near impossible to access otherwise, and someone who knows him is keeping an eye on him on a regular basis."

The Government's 10-Year Health Plan has made prevention a key priority, and Connie believes community schemes will be instrumental in its success: "We need schemes like ours to be proactive in primary care.

"Many of our elderly patients feel left behind by digital technologies and some minority groups can also feel as though they're excluded or unable to utilise our services. Contact with someone who is affiliated with the local GP practice and part of the local community breaks down barriers between us and patients, allowing us to identify and treat conditions sooner."

It's the sense of trust that the pilot has fostered that Connie believes is the keystone of its success.

"For the original pilot, it took on average eleven knocks to make contact with a patient. However, once we made that connection and the CHWWs had those initial conversations we started to see the benefits. There was encouraging uptake with services like health checks and vaccinations - when on a national level, engagement rates with vaccine programmes have been falling," she explains.

Despite its benefits, Connie is concerned that funding constraints will be a barrier to wider implementation of the programme: "Our trial has been successful and we've seen other areas adopt similar programmes, but it does take time to establish and when funding is reviewed on an annual basis, it can often be pulled before we see the benefits.

"We need to allow initiatives to grow at their own pace and be allowed to make mistakes. It takes time to bed in, and we need to be willing to maintain these programmes, to trust the data, invest in the community and allow it to flourish,” she says.

"Our job as GPs is more enjoyable when we have connections with our patients, when we have a clear idea of what is going in their lives. We need to avoid becoming transactional with our care, this initiative pivots our care back to the community and allows for those crucial early interventions."

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.