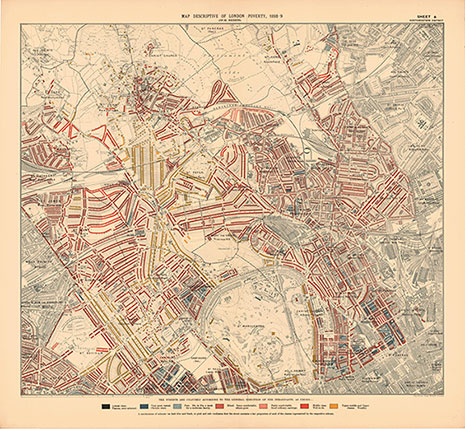

Banner image: Booth Map North Western. Map descriptive of London, North Western District, Charles Booth, 1898-9. To explore the maps in detail, visit the LSE website.

Nineteenth-century doctors showed great concern for the social and economic factors affecting urban health. The first Medical Officer of Health (Moh) in the UK was Liverpool GP William Henry Duncan, appointed in 1847. Duncan campaigned tirelessly for improvements in housing and sanitation, aware of the impact on the health of his patients.

Step back into time

This extract is from evidence submitted to Edwin Chadwick’s Poor Law Commission in 1840. Duncan, a GP in Liverpool, became the first Medical Officer of Health for the city in 1847.

"There can be little doubt that the causes of the unusual prevalence of this disease [fever] in Liverpool are to be found principally in the condition of the dwellings of the labouring classes, who are almost exclusively its victims; but partly also in some circumstances connected with the habits of the poor. With regard to their dwellings, I would point out as the principal circumstances affecting the health of the poor:

- Imperfect ventilation

- Want of places of deposit for vegetable and animal refuse

- Imperfect drainage and sewerage

- Imperfect system of scavenging and cleansing

The circumstances derived from their habits most prejudicial to their health I conceive to be:

- Their tendency to congregate in too large numbers under the same roof etc.

- Want of cleanliness

- Indisposition to be removed to the hospital when ill with fever.

Local reports on the sanitary condition of the labouring population of England, in consequence of an inquiry directed to be made by the Poor Law Commissioners." Presented to both Houses of Parliament, by command of Her Majesty, July 1842. Available online from the Wellcome Library.

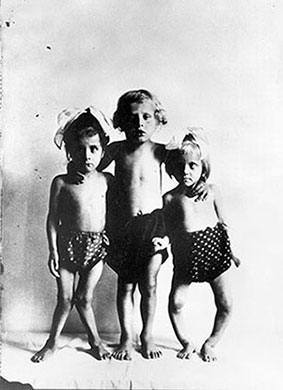

“Children may, and in fact not infrequently do, grow up healthily in spite of a bad material environment. They may avoid clinical illnesses due to infections, though exposed to the infections; they may survive, undamaged, illnesses resulting from the invasion of their tissues by pathogenic microorganisms, but they cannot survive unscathed prolonged deprivations or deficiencies of certain essentials for normal nutrition.” (Poverty and Public Health, p. 148)

Julian Tudor Hart was a GP in a former mining village in South Wales for 30 years. His ‘inverse care law’ and his public health work in Glyncorrwg feature heavily in the exhibition. He was interviewed in 2015 by Robert McGibbon and Sharon Messenger.

"I think the College ‘Cum scientia caritas’ is fine, it’s quite a useful idea, but it’s not really very exciting, now. But it seems to me that the idea, if it could be expressed briefly, there is no such thing as natural justice. Natural justice doesn’t exist. Nature is very unjust, we introduce the idea of justice, it’s a human concept, and it has to be implemented like that. We have to create justice, and there’s nothing wrong about that. It’s not saying that we dominate nature in the sense that people did when they were recklessly chucking carbon into the air and so on, it’s something we should be proud of. And the College ought to stand for that, that it wants more justice, you know, illness should be less unjust in its distribution. Sure, eliminate it if you can, then we could address the most difficult problem of all the problems that I can think of, this business about how we die. How we have a time to die, because undoubtedly, we’ve got to move out the way. The people who talk about thousand year lives, things like that, I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous and so immoral. Uh, get out of the way! You know we look at our children, and we want them to take over, they’re better people than us - they so bloody well should be, you know! We’ve done so much work, they’re building on what we did, so shouldn’t they be ahead of us?"

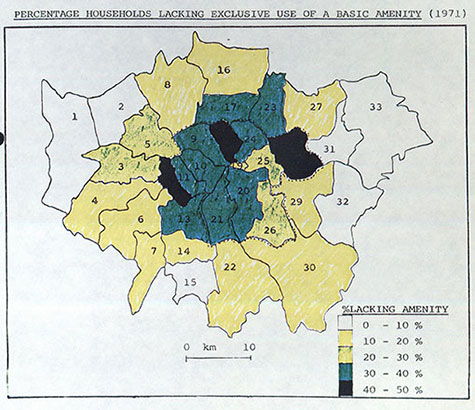

Brian Jarman was professor of primary health care at Imperial College London from 1983 – 1998. In this interview with College President Denis Pereira Gray in 2010, he talks about the introduction of his underprivileged area score in 1990 – which became commonly known as the Jarman Index.

"The idea was to give pay in the inner-city areas in proportion to workload so that each GP got the same pay per unit of work – not an easy thing to do. And they decided that meant that the majority of GPs would be worse off and so it wouldn’t work. However, John being a fair person as I left the room he said come back Brian, we’ll give you one chance. If you come back in 3 months’ time, we will choose 5 areas randomly and we will ask the GPs at the LMC to shade the electoral wards according to the degree to which the patients in the area increase their workload or pressure on their services. And when we meet in 3 months we will see if there’s any overlap. And when we looked at the maps, there was only 1.4 or 1.6% of pairs of wards differed. So I then went for my first ever LMC GP conference at the Logan Hall. You have two minutes to speak … And I put it forward and they voted, having seen these figures, unanimously to accept the methodology. Purely theoretical, nothing happened, until 1990, the new White Paper – I suppose the Thatcher White Paper on primary care – came out and the day before, three parts of the department of health ask us for underprivileged area scores so I realised that they were going to use them. And they started paying GPs on that basis."

Peter Brent was a GP at a practice in Wembley and Willesden in London in the 1960s and 1970s. He was interviewed for the College in September 2019.

“And at that time in the area where we lived it was a fairly deprived area so patients didn't have cars, most of them, a lot of them didn't have phones which meant that they had to, if they needed a doctor, they had to go out and find the nearest working phone box to phone us. So generally, if they've, if that was necessary it was usually a definite requirement that they needed to see a doctor. We didn't in the early days, we didn't have any mobile phones of course and when we went out on the way home, we dropped into the nearest police station and said do you mind if we phone to the call service to see if we have any messages before going home to see if there were any more calls. So, we got to know the police pretty well.”

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.