In 1878, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson contributed a chapter for women students to "The student's guide to the medical profession". She advised “tenacity of purpose” and “unwearying industry”, to dress inconspicuously, and to include recreation in each week such as tennis, swimming or attending concerts with friends.

By the 1920s, the Medical Women’s Federation were promoting general practice as “a role for which women are peculiarly well-fitted.”

In more recent decades, an emphasis on flexible training and working, equal pay and opportunities, and a healthy work-life balance has gained in importance alongside exploration of the issues making certain specialties more attractive to women than men.

“The department of medicine in which the great and beneficent influence of women may be especially exerted, is that of family physician; and not as specialist, but as the guides and wise counsellors in all that concerns the physical welfare of the family.” Elizabeth Blackwell, 1889

“Well, I think, in my case, I was just lucky that they needed doctors so badly, in general practice just after the [Second World] war, they’d take anybody. Perhaps there weren’t enough women doctors to go round, I really don’t know about that, I never had the slightest problem, or the slightest interest or feeling about women’s issues, I’m afraid, as a result, yes… I think we were very lucky.” Elizabeth Horder, 2013

“I didn’t want to be a lady doctor, I just wanted to be a doctor...” Woman GP, 1960s

Key dates

1874 the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) opened, the first British school where women medical students could receive a full clinical education

1947 as a result of the Goodenough Committee (1944), all London medical schools were obliged to take women students

1969 the Married Women’s Training Scheme, providing flexible medical training for women with domestic commitments, was rolled out nationally

1975 a new government retainer scheme, introduced in 1972, was extended to general practice, allowing women doctors to reduce their training and clinical work commitments

People

Find out more about individual women’s experiences by clicking to expand.

Jane Walker (1859-1938) pioneered the treatment of tuberculosis, establishing the first British sanitorium for outdoor treatment in Norfolk in 1892. However, as a young woman who aspired to a career in medicine, her options were limited. With her father’s support, she studied at the recently-opened London School of Medicine for Women. However, women were unable to take a medical degree in Britain, and so she ultimately gained an MD in Brussels in 1890.

Like many women doctors of her generation who had sufficient wealth, general practice for women and children patients was the starting point of her career. She described opening a private medical practice at her home on Harley Street as a ‘nerve-wracking experience.’ She joined Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s New Hospital for Women, firstly as an outpatients’ physician in 1888. Even when tuberculosis became her primary focus from the 1890s, she retained her private practice.

Dr Walker was the Medical Women’s Federation’s first President in 1917, committed to representing the views of medical women. The MWF, still a vibrant organisation today, has spent over a century campaigning for better working conditions for women doctors, and providing a strong supportive network.

Image: Dr Jane Walker, Association of Registered Medical Women, 30 January 1917. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Rosemary Rue (1928-1994) was inspired to study medicine by her childhood experience of tuberculosis and peritonitis. However, following her marriage in 1950, the LSMW refused to allow her to complete her training. She qualified in 1951 in Oxford, taking a first job in geriatrics. Despite managing to juggle this with a new baby, after three months she was sacked for being married and a mother. At this time marriage bars were in place across many professions, including some medical roles. Even without this formal barrier, a MWF survey carried out in 1965 showed that 60% of married women doctors with children were not working in medicine.

Although the number of women medical students was increasing significantly, the expectation of fully-residential hospital training posts was incompatible with raising a family. Large numbers of women were dropping out of medicine. Dr Rue found general practice more accommodating than a hospital role. She recalled “patients were extremely nice and they minded him [her toddler] or talked to him or some member of the family would talk to him or show him the farm or something while I saw the patient.” She suffered another significant set-back when she contracted polio, the last case reported in the Oxford area.

After a long period of rehabilitation, Dr Rue re-entered general practice before moving into public health. Among many other achievements, she devised the first scheme to allow women doctors with children to work part-time while in training. Starting locally, she established the Married Women’s Training Scheme, which was later adopted and promoted by the BMA and MWF. It was rolled out nationally as a flexible employment and postgraduate training scheme in 1969.

Image: Dame Rosemary Rue. Credit: Oxford Medical Alumni.

Stories

Lady-Physicians

Punch published this cartoon just after Elizabeth Garrett registered as a doctor in 1865. In it, ‘Reginald de Braces’ appears to have caught a bad cold as an excuse to send for a woman doctor.

Early women doctors were well aware that their gender prompted concerns both about decency and their capabilities. They argued that women patients needed women doctors so that they could choose not to be seen by male physicians. It wasn’t until later in the twentieth century that it became socially acceptable for medical women to treat men.

Image: Punch, 23 December 1865. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Supporting women in general practice

Careers advice for potential doctors developed significantly from the 1960s onwards as working options increased and more specialist training programmes were introduced. However, the issues surrounding balancing medical work and family life, flexible working and part-time training loomed larger than ever within national discussions about equal pay.

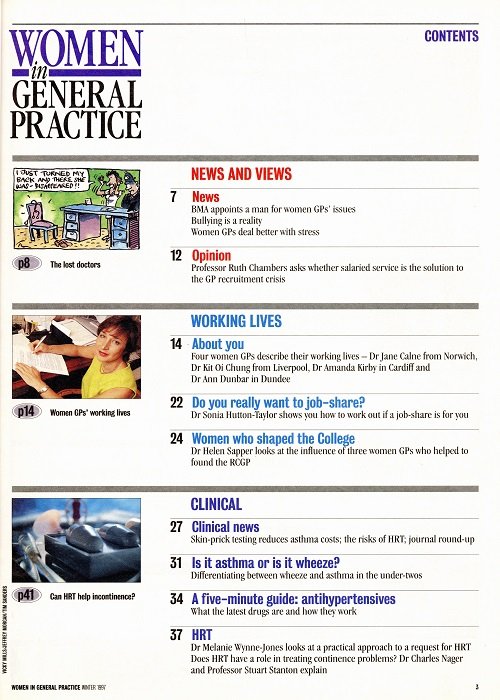

By the early 1990s, there were more women College members under the age of 30 than men, but they were also the group leaving the profession at the highest rate. Dr Mollie McBride (1931-2013) as the College’s Honorary Secretary played a key role in initiating joint working with the MWF to look at the issues facing young women GPs. In 1993 a Women in General Practice Task Force was established by the College, chaired by Dr Sarah Jarvis. The journal Women in General Practice was launched in 1997. In 2012, the College gained approval from Medical Education England to extend GP training from three to four years, allowing for a degree of greater flexibility.

Image: This contents page of the first issue of Women in General Practice from 1997 indicates some of the current issues.

Voices

Listen to our audio clips as Helen Bayliss reflects on her motivation to study medicine, Sally Hull reflects on her realisation about the perception of women doctors and general practice, and Gill Yudkin remembers job-hunting advice from a misogynist tutor.

Transcripts

Discover the exhibition

Find out more about the history of women in general practice by visiting our Women in GP exhibition.

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.